2 stars (out of 5)

By R. Kurt Osenlund

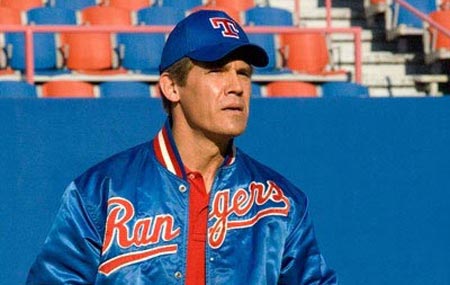

Superheroes may have ruled the summer blockbusters, but Nazis are the suited figures dominating cinemas this winter. By year's end, more than five major films themed around some aspect of Nazi Germany will have been released, including “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas,” “Adam Resurrected,” “The Reader,” “Defiance,” and “Good.” Bryan Singer, who's perhaps best known for helming the Oscar-winning cult classic “The Usual Suspects” but more recently notable for taking on projects like “X-Men” and “Superman Returns,” should have stuck with the warm weather pack. His Hitler-assassination thriller, “Valkyrie,” which has him directing Tom Cruise in the fading star's latest futile attempt at a comeback, is sure to be the worst of this Reich-ridden lineup. Burdened by Cruise's misguided, distractingly self-important performance, it's a shoddy, Hollywood-ized take on an otherwise fascinating true story.

Cruise is Nazi Colonel Clauss von Stauffenberg, a key player in the German Resistance movement and the key player in a film that's loaded with characters who have very German names but are portrayed by very not-German actors. In “Valkyrie”'s opening sequence, Stauffenberg, while on patrol in the deserts of Africa, is severely wounded in an aerial attack. The incident costs the colonel his right hand, a few fingers, and his left eye, forcing him to wear a pirate patch and giving Cruise the opportunity to once again pursue character depth via facial disfigurement (see “Minority Report,” “Vanilla Sky”). It also facilitates Stauffenberg's traitorous-but-noble desire to dethrone Hitler (played by relative unknown David Bamber), a man who, in July of 1944 when the film is set, had become “not only an enemy of the world, but an enemy of Germany.”

In Stauffenberg's corner is a handful of high-ranking military men, all of whom have similar minds for treason and most of whom are played by classically-trained Brits. There's Major-General Henning von Tresckow (Kenneth Branagh), who takes an early crack at offing the Fuhrer with a killer Cointreau bottle; General Friedrich Olbricht (Bill Nighy), who shapes up to be Stauffenberg's closest ally; General Ludwig Beck (Terrence Stamp), a behind-the-scenes asset with copious political influence; and General Friedrich Fromm (Tom Wilkinson), a shrewd coward playing both sides. With none of these men up to the task, Stauffenberg assumes the responsibility of taking out Hitler himself by hand-delivering plastic explosives to one of the dictator's wooded outposts. He code-names the mission Operation Valkyrie after Germany's Reserve Army, which is meant to be employed to intercept a rebellion against the government but is instead duped into expediting one.

The best thing about “Valkyrie” is that it gets right to the point. It wastes very little time with potentially taxing backstories and/or broad coverage of WWII and instead leaps right into the task at hand. Sadly, that's about as far the movie's observance of audience concerns goes. Stauffenberg's actual act of planting the bombs is the only portion that generates any real suspense. The remaining chunk is a by-the-numbers exercise in stale plotting and studio standards. The disappointingly stock script by Oscar winner Christopher McQuarrie (“The Usual Suspects”) and first-timer Nathan Alexander is peppered with flagrant foreshadowing and oh-no-they-didn't dialogue. In the first half especially, nearly every scene is capped off with an over-emphatic exit line plucked right out of Hollywood's bargain bin, such as, “Only God can judge us now,” and, “This is a military operation – nothing ever goes according to plan” (no need for the “duh-duh-duh” music; the actors have that area covered). Two of this year's best movies, “Man on Wire” and “Frost/Nixon,” also gave accounts of well-documented historic events, but did so with smart and breathless pacing that created tension despite viewers' knowledge of the outcomes. “Valkyrie” fails to achieve that same urgency because it's so clearly a commercial concoction, led by none other than Tom Cruise.

I imagine that this movie will infuriate many Germans, especially those few who survived and/or sympathized with the events depicted. With Cruise as the conductor, any cultural authenticity is hopelessly derailed. Speaking in his American-as-apple-pie-voice and sticking out like a sore thumb among a cast of Europeans (at least the Brits are from the right side of the pond), the former box-office king feels about as alien to this picture as his space-cadet religion must feel to his fans. His presence is hulking and bizarre, further stripping the film of its prestige and revealing it as a shameless star vehicle. If his involvement is not part of his own effort to revamp his waning career, then what is he doing here? Surely the director didn't take on a film about Nazi Germany and immediately think to call Tom Cruise. I've long prided myself in the ability to separate stars' public images from their work on screen but Cruise is my Kryptonite. His peculiar paparazzi persona now follows him into the film frame, irrevocably blurring the line between the personal and the professional. If he's ever able to reestablish that divide and make a triumphant return worth watching, I'll be there, but “Valkyrie” ain't it.

The few German actors who do appear in this film are given blink-and-miss bit parts. The lovely and talented Carice Van Houten (“Black Book”), who plays Stauffenberg's wife, Nina, has about eight lines and is assigned such not-so-subtle actions as gripping her belly to let us know she's pregnant. Another is East Germany-born Thomas Kretschmann (Peter Jackson's “King Kong”), who's cast as Reserve Army leader, Major Otto Ernst Remer, and handed some of the screenplay's more priceless gems. Take this beaut, which he barks at a courier who's repeatedly brought him false alarms: “In ancient Greece, you would have been killed for this,” he says. “Lucky for you, we've evolved.” Yeah, thanks. It's a good thing the brains behind “Valkyrie” never lived in ancient Greece.